I paced up and down the isles of my local branch of Hobbycraft, hawk-eyed for the sketch-book section, keen to treat myself to a new pad of 120 gsm, into which I would scribble ever more architectural dreams. I had the same feeling I get when wondering unaccompanied around National Trust properties – that of being an anomaly in a place. I did not conform to the stereotype that exists in this institution. I was twenty-two and male, what was I doing here? The second glances from elderly ladies confirmed as much. All around me were sequins and fabrics and glues and tassels and kits and paints and brushes and needles – a seemingly endless array of ‘craft’ supplies. This place defines only one type of craft, but it is an important type, as it is descended from what true crafts used to be: the carpenter, the cobbler, the tailor, the blacksmith, the list goes on.

All the skilled crafts that were still flourishing not a century ago have since been displaced by the advent of the digital age. Now thousands of products can be machine manufactured at minuscule cost over and over again until someone designs next year’s range, discarding the old designs as unfashionable and out-dated; but how is this related to architecture?

The last time craft really existed in its conventional sense in architecture was back in the 1890s and 1900s with the Arts and Crafts movement. The principles of this movement, championed by men such as William Morris and Charles Voysey, were to find aesthetic design and decoration based in truth of materials and hand crafted production. It was a reaction against the machine produced buildings and associative styles that were beginning to dominate. As we know, Modernism took hold of mainstream architecture and only now, over a century later, are we seeing hints of its demise; but where does craft come in?

Any of the few remaining craftsman will tell you that what they do is produce high quality goods slowly and with a very high level of skill. When we think of craft we always think of manual skills where a craftsman physically produces the products himself. However, anyone who has produced a highly detailed 3D computer model of a product or a building will know that it takes a great deal of care, time and most importantly skill. Is this not also a skilled craft? The traditional craftsman is skilled in using the tools he has - so too is the 21st century designer with his or her tools. The only difference is the nature of the tools.

Hang on though, it still takes a team of builders or manufacturers to produce a product from the computer designs, no matter how ‘crafted’ they are. Well that may not be the case for much longer. We can already print small items straight from the model with 3D printers. It doesn’t take a genius to extrapolate the technology and conclude that one day we will be able to print entire building components straight from our computer models. The software will determine what can be printed and what needs to be cut from raw materials, such as tree trunks and stone blocks. It would attach all the service components and finishes prior to the building component leaving the factory. It would then generate assembly instructions for all the component parts which could be assembled in a matter of days on site.

This already exists to an extent with kit houses, but there are two key differences. The first is that the panels for kit houses still need to be built by hand in a factory. The duration of the work is effectively the same but a lot is being done off site – direct computer assembly will do the same thing but in a fraction of the time. This sounds rather like Modernism all over again. Where does the craft come in?

That brings me to the second difference that ‘direct-from-model’ manufacturing would bring about. The shaping possibilities of computer modelling have already been demonstrated in contemporary architecture, Zaha Hadid’s work being the obvious example. What complex computer modelling has yet to be applied to though is small scale ornamentation and decoration – the realm of the traditional craftsman. A shape could be generated in a computer model, and then carved out of wood or stone directly with a milling machine. Customised steel beams could be designed and printed based on the specific structural needs of a building, with the computer showing the exact force lines and the designer forming a beam around them. Organic compound panels could be printed in an endless array of shapes. The possibilities are huge.

Pugin had it right when he said ‘there should be no features about a building which are not necessary for convenience, construction, or propriety’ and ‘all ornament should consist of enrichment of the essential construction of the building’. These principles are becoming more and more relevant with the slow downfall of modernism, and we have already begun to see a return to complex architectural formwork in this respect. The contemporary reinterpretation of it is organic architecture, such as that championed by the likes of atmos studio’s Alex Haw. Haw may or may not agree with Pugin’s principles, but his ‘style’ if it can be called that, is the future of mainstream architecture.

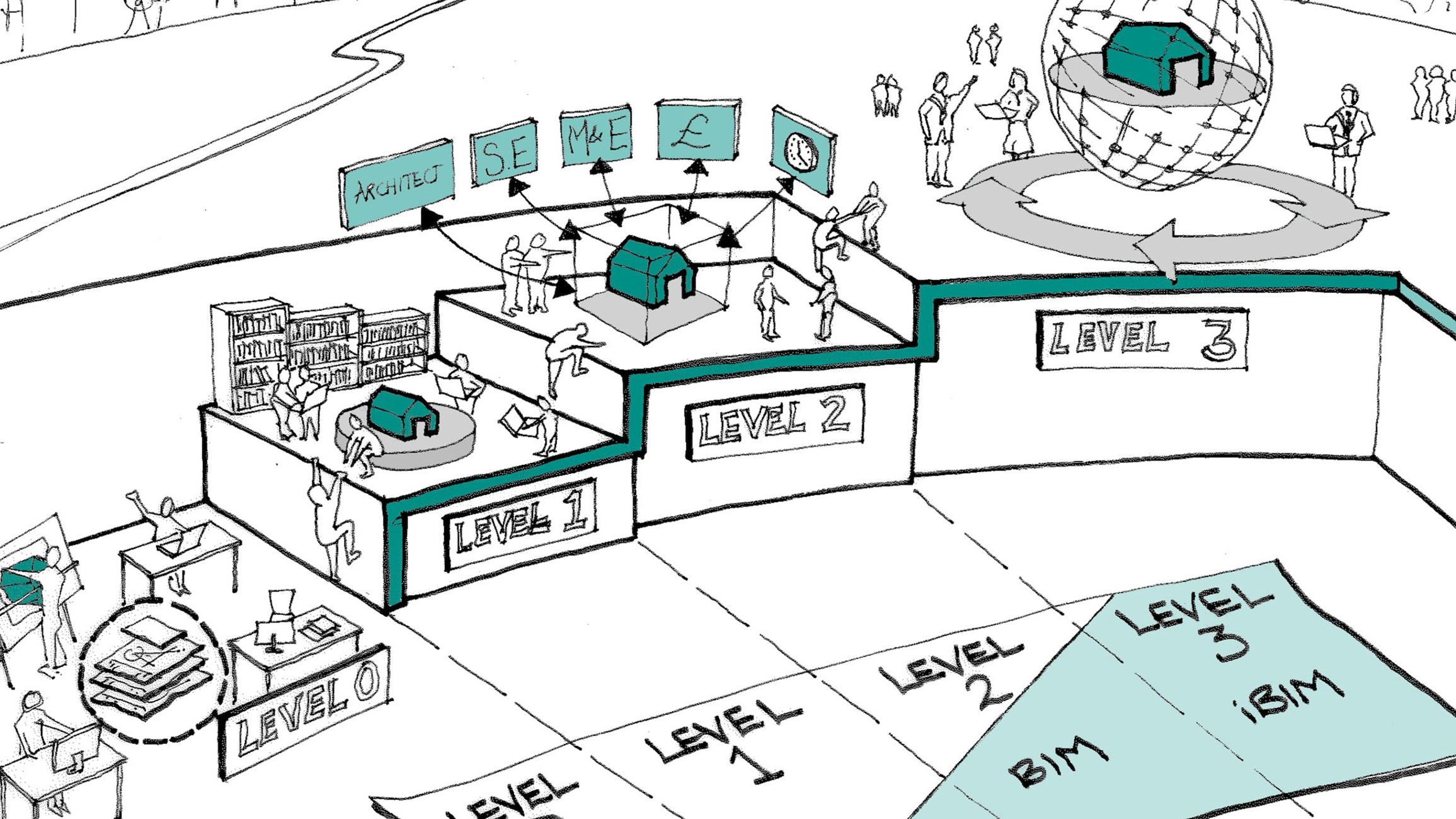

The domestic developers though will take a lot of coaxing out of their precious Neo-Georgian. When they eventually join the 21st century, they will be able to apply Pugin’s principles and Haw’s ‘style’ to create some truly wonderful buildings. Craft is returning, not in wood-chip, ironwork or leather, but in 3D modelling, 3D printing and computer assembly. The seedling of this revolution is BIM, so embrace it now and you too will one day be considered a skilled craftsman.

Bruce Buckland is Founder and Director of Buckland Architecture.