There is certainly no shortage of awards in our industry to which the budding architect can aspire. Fuelled partly by the tendency in all professions to seek self-congratulation, and partly by an assortment of magazines, blogs and websites jostling for attention in a crowded marketplace, the panoply of awards with which we find ourselves is sucking dry our limited pool of attention and interest. It is in this context that the few remaining big hitting awards must ever more assertively wade through the festering swamp of bitter applause, and climb the jagged mountain of laser engraved cabinet fodder to reach the holy grail of respectability; a poison chalice only held by properly gaining the attention of that most weary of creatures – the public.

Within the creative industries there are only a handful of awards that the average half-decently educated person has ever heard of. Amongst these are the Turner Prize for art, the Booker Prize for literature, and the Stirling Prize for architecture. Whilst the first two of these continue to command extensive media attention and at least a respectable degree of wider public interest, the Stirling Prize is slipping further and further off the public and media radar. From an hour long prime time slot on BBC 2 a few years back, it is now a side note on the BBC News channel, one of those items that fills the gaps between reporters repeating themselves every fifteen minutes. The ceremony is not even a dinner anymore – how are self congratulating practitioners supposed to parade their egos around when their peers are not even forced to endure an entire meal for the privilege of witnessing it.

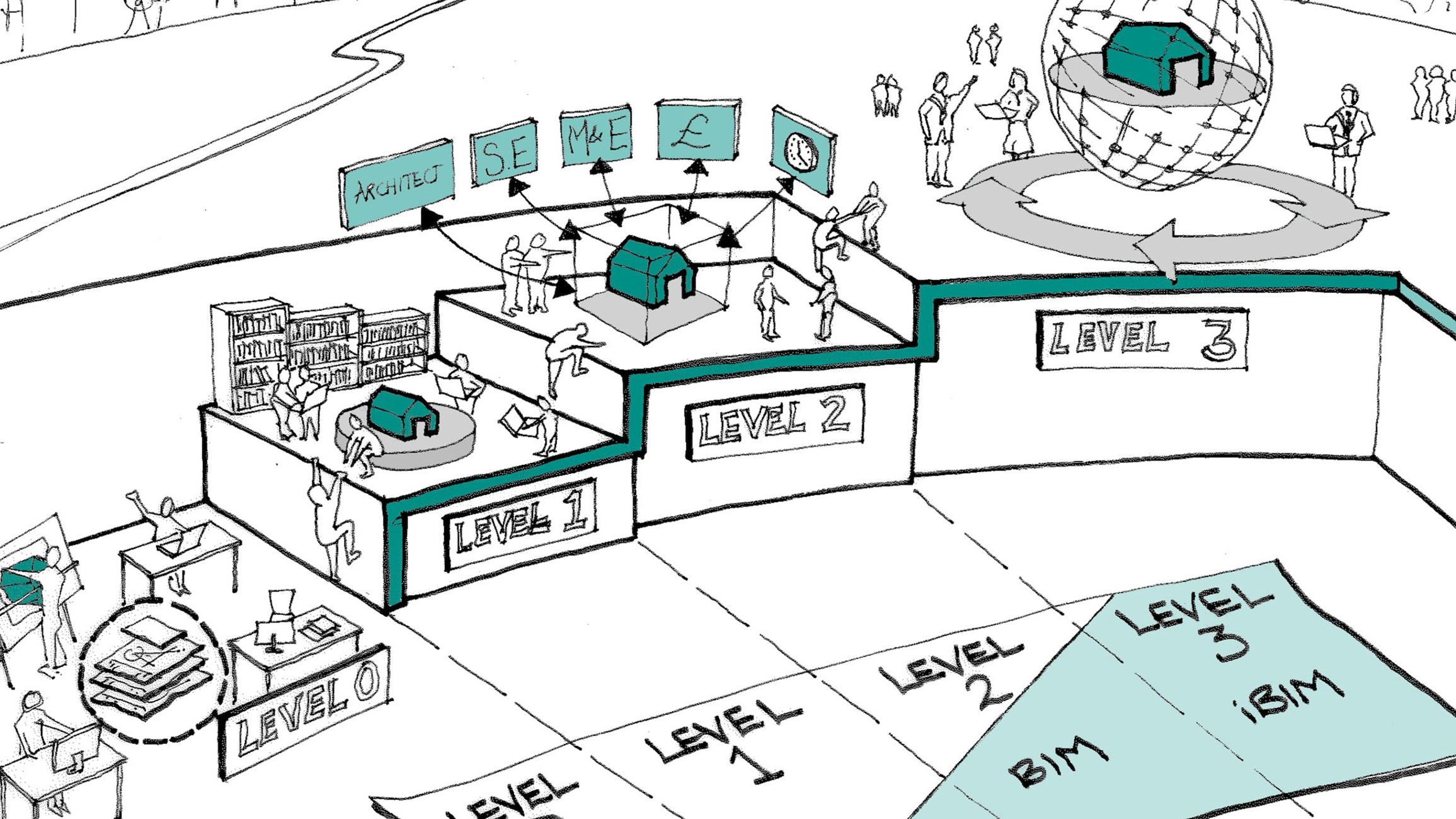

Recently the newly rebranded ‘RIBA House of the Year Award’ (formerly the Manser Medal) was won by Skene Catling de la Peña’s ‘Flint House’. An impressive building this most certainly is, commanding its immediate vicinity with a ziggurat landscraper monumentality, essentially enriched with a lapidarian skin; one unfortunately less evident internally. Tectonically it manages to mostly, if not entirely, avoid the major common faux pas of contemporary pseudo-modernist new builds. Its lack of pilotis and escape from excessive rectilinearity do it much favour, though its evident façadism shows that it has not entirely transcended contemporaneous fads.

Above: The Flint House, Waddesdon. Architect Charlotte Skene Catling. Sent for Oliver Wainwright piece, one time use for this purpose only

Hope has, however, in one guise at least, risen its glittery head in recent weeks. The Turner Prize, bastion of avant-garde ‘art’ as it is, has unexpectedly been turned upside down by its awarding to architectural collective Assemble. There has been much debate within the profession as to whether this signals architecture’s great return to the sphere of public attention, or whether it indicates yet another stop on the long road to professional irrelevance and the defining of architecture as mere prettification, largely irrelevant to the serious business of building.

Whether one, both, or neither of these is the case to any degree, what can certainly be said is that it has put architecture once again back in the minds of at least a handful more people than previously. Perhaps these very same people, armed with their refreshed intellectual engagement with architecture, will go forth into the world and use it for the betterment of society more widely, say, for example, with the ‘Skylines’ campaign for better tall buildings in London, or the various campaigns for better quality housing. We should not, therefore, be cavalier or condescending about the ‘wrong kind’ of public engagement in architecture. In truth we are not in a position to be picky. Any kind of engagement, even if not ideal, is better than almost total irrelevance or absence in the minds of the public.

There are deeper questions however, of precisely why it is that contemporary architecture figures so little in most people’s lives. As much as many practitioners may recoil at the suggestion, most studies done on the public’s taste in architecture indicate that those buildings displaying characteristics usually associated with the Modern movement are far less popular than those with more vernacular or historical styles. Quite why this is so is an incredibly complex question, and requires far greater engagement from the profession if it is to recapture the attention and the admiration of the public.

So long as we are responsible in the public’s mind, for structures with which they do not feel they can engage, connect or identify, we will forever remain an irrelevance. We must ask ourselves, at the most fundamental level, what is it that makes a building loved by the everyman and every woman on the street? What is it that turns architecture from aesthetic white noise into a harmonic urban symphony? And, where the public is concerned, what can we as a profession change to bring architecture back into the forefront of the public’s consideration and imagination? These are questions that must be answered if architecture is to remain both progressive and socioculturally sustainable for the foreseeable future.

Bruce Buckland is Founder and Director of Buckland Architecture.